Shift from Polls to Mail Changes the Way Americans Vote

More Americans than ever are expected to vote by mail

rather than go to polling places in November.

A gradual loosening of absentee voting laws in many

states, especially in the West, and universal mail

voting in Oregon and Washington have contributed to a

significant shift in how Americans vote.

Almost 16 percent of votes cast in the 2010 general

election were absentee ballots and nearly 5 percent

more were mail ballots, according to the U.S. Election

Assistance Commission’s Election Administration and

Voting Survey. In 1972, less than 5 percent of American

voters used absentee ballots, according to census data.

When mail or absentee voters were combined with

in-person early voters, nearly 30 percent of the

Americans who voted in the 2010 general election did

not go to the polls on Election Day, according to the

federal election survey.

“By 2016, casting a ballot in a traditional polling

place will be a choice rather than a requirement,” said

Doug Chapin, a University of Minnesota researcher and

director of the Program for Excellence in Election

Administration.

“There will still be people who go to the polling place

because it’s familiar, it’s convenient, it’s

traditional. I think there will be fewer of those

places. More and more people don’t vote on Election

Day,” Chapin added.

In the partisan controversies in 37 states over recent

changes in voter eligibility, the number and location

of polling places, how elections are monitored and the

hours that polls are open, the growth of no-excuse,

absentee voting and mail voting has received little

attention.

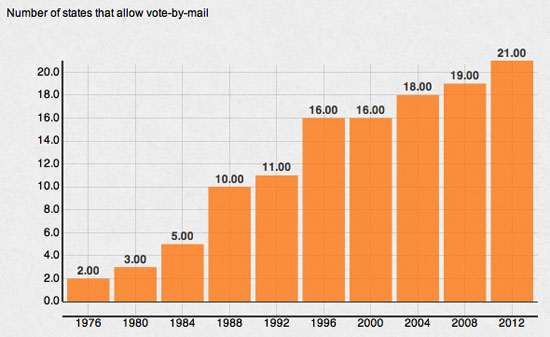

Click on the image to see an interactive showing the

growth of mail voting and absentee ballots.

Western states tend to have the highest levels of

absentee voting, according to the Election

Administration and Voting Survey. Those levels reached

almost 70 percent in Colorado and 60.8 percent in

Arizona, according to the survey. More than 20 percent

of people used absentee ballots in 13 states, according

to the survey.

East of the Mississippi, the mail is more likely to be

a back-up option for those who can’t get to the polls

on Election Day. That’s the case in 15 states,

including New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia,

according to the National Conference of State

Legislatures.

John Fortier, a political scientist of the Washington,

D.C.-based Bipartisan Policy Center, has called the

shift away from the polls a voting revolution that is

fundamentally transforming elections.

“It’s not something we’ve fully thought out all the

consequences of, and we certainly haven’t had one big

national debate over it,” said Fortier, author of

Absentee and Early Voting: Trends, Promises and Perils.

“Even some state debates were not as robust as they

might have been.”

Proponents say the mail offers voters time to weigh

choices and flexibility for their busy schedules, even

more so than early in-person voting. It reverses how

elections work, said Phil Keisling, former Oregon

secretary of state and director of the Center for

Public Service at Portland State University.

“The default is bringing the ballot to the voter, not

forcing the voter to go to the ballot,” Keisling said.

Putting a ballot inside an envelope and sealing it

inside another envelope for mailing still stirs

skepticism, though. Election officials, political

scientists and voters have concerns. They doubt that

mailed ballots can be secure. They question whether

forces beyond voters’ control — smudges that disqualify

ballots and breakdowns in keeping track of ballots, for

example — will disallow votes. And some want to

preserve Election Day traditions.

Changes have occurred gradually to absentee voting,

which began as a service to Union and Confederate

soldiers during the Civil War and spread to civilians

state by state.

Few paid attention when California extended absentee

voting to anyone on request in 1978. The Los Angeles

Times referred to a “little-noticed law” that

eliminated the need to list a reason to get an absentee

ballot. In the 2010 election, 40.3 percent of

Californians voted absentee, according to Election

Assistance Commission data.

Now, 27 states and Washington, D.C., offer no-excuse

absentee voting, according to the National Conference

of State Legislatures. Many states have dropped notary

and witness requirements for all absentee voters. Plus,

some have permanent absentee lists to automatically

send ballots to voters in every election, a de facto

vote-by-mail system.

Most states have opted for a mixture, offering some

combination of no-excuse absentee voting, early voting,

mail voting and Election Day voting. These categories

often blur and overlap. A voter might drop off a ballot

in person instead of mailing it, for example.

“It has to do almost entirely with voter convenience,”

said Jennifer Drage Bowser, a senior fellow at the

National Conference of State Legislatures. “The more

options there are outside the traditional polling

place, the more voters like it.”

Those options vary by region.

All Washington and Oregon elections are conducted

statewide by mail. In Washington, each county still

maintains at least one voting center. In Oregon, each

County Elections Office provides privacy booths for

those who want to vote in person or need assistance.

Oregon approved a test of vote-by-mail in 1981, and

about 40 percent of Oregon voters used absentee ballots

in the 1994 federal election. By the next year Oregon

statewide elections with candidates were by mail, and

in 1998 the state voted for all elections to be by

mail. Washington, where absentee voting was similarly

popular, tested voting by mail and used it in all but

one county until the state adopted all-mail ballots in

2011.

There’s a generation of voters who never have set foot

inside an Oregon voting booth.

Jessica Hall, 32, has 2-year-old twins and runs a home

business. She always has voted by mail; Oregon switched

shortly before her 18th birthday. She makes better

decisions, Hall said, than if she had to stand in a

long line outside a polling place. In the evening, when

her children are asleep, Hall sits quietly and reads

her ballot, then votes.

“Without vote-by-mail, I would be less likely to vote.

I don’t have time,” Hall said. “There’s no way my kids

would allow me to stand in line and do that.”

North Dakota counties can decide whether any of their

elections should be conducted by mail. Eighteen other

states allow vote-by-mail in some cases — uncontested

Arkansas primaries with no other ballot measures, for

example.

Jan Leighley, a political scientist at American

University, offered culture and population density as

possible explanations for the low popularity of

absentee/mail voting in the East. Eastern and

Midwestern states tend to have more established, formal

political parties — a culture resistant to changing

voting modes, Leighley said.

In widely dispersed populations in Western states,

voters and election officials have more to gain by

using mail, Leighley said. They wouldn’t have to pay to

operate scarcely used polling places, and voters

wouldn’t have to travel as far to cast a ballot.

New Jersey has allowed mail ballots on request since

2005, but fewer people are using them than expected,

said Robert Giles, director of the New Jersey Division

of Elections.

About 5 percent of New Jersey votes were by mail in

2010, compared with about 4 percent in 2005, according

to a report from the elections division.

“Going to the polls, I think it’s ingrained in our

society,” Giles said about the slow growth of mail

voting in his state. “For some people, there’s a social

aspect. They see the same election board workers every

time they vote, and it offers a sense of community.”

Concerns about ballot security have stopped other

states from adopting more mail voting. Both sides in

the voter fraud debate acknowledge that absentee

ballots are susceptible to fraud.

Election fraud is rare, but it usually involves

absentee or mail ballots, said Paul Gronke, a Reed

College political scientist, who directs the Early

Voting Information Center in Oregon. He cites what he

calls a classic example of election fraud, a local

official stealing votes by filling out absentee

ballots. That was the case in Lincoln County, W.Va.,

where the sheriff and clerk pleaded guilty to

distributing absentee ballots to unqualified voters and

helping mark them during a 2010 Democratic primary.

Curtis Gans, director of the Center for the Study of

the American Electorate, said vote-buying and bribery

could occur more easily with mail voting and absentee

voting. At a polling place, someone who bribed voters

would have no way to verify that the bribe worked. A

person who bribes mail voters could watch as they mark

ballots or even mark ballots for them.

Gans also points to the potential to influence voters

in gatherings that some call ballot-signing parties. A

caregiver could mark a dependent’s ballot.

“All the other types of fraud are essentially hard to

do and easy to defend against,” Gans said. “This

isn’t.”

Gronke said that he hasn’t seen evidence that bribes

and coercion increase when voters use the mail. And

ballot parties can allow people to discuss and make

informed choices, he said, without pressuring their

vote.

Those who have argued for stronger election security

also say the mail could allow coercion by an abusive

spouse; Gronke said he sees little evidence of that.

Mail benefits outweigh potential fraud, supporters

said.

“If you try to literally kill everything in your body

that may kill you, you will definitely die,” Keisling

said. “If you try to wring every possibility of

mischief and fraud out of a voting system, you will

cramp it down so hard that very few people will end up

voting.”

Some see mail as a step backward from the Help America

Vote Act of 2002.

Charles Stewart, a political scientist at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said the law

mandated improved voting equipment. That improved

technology made vote counts more accurate, he said,

leading to 1 million more votes being counted.

Mail ballot procedures have not been improved, Stewart

said, estimating that errors such as pencil smudges,

errant marks or breakdowns in keeping track of ballots

can mean up to 7.6 million mail votes could go

uncounted. Machines prevent voters from casting errant

ballots, he said.

“The two sides of that equation just don’t balance

out,” Stewart said. “Many more ballots are sent out

than come back.”

Mail voters could base their decisions on different

information than those who go to the polls, Gans said.

And voting before Election Day leaves open the prospect

for voters to turn in their ballots, then see a stock

market crash or terrorist attack and wish they could

change their votes, Gans said.

A longer window until voting time, however, means

people can vote more carefully and make better-informed

decisions, Keisling said.

Organizations such as Mi Familia Vota, a national

non-profit that advocates voting rights, encourages

Latinos to sign up for permanent absentee ballots so

they have more time to choose.

The mail also means campaigns can’t count on a final

push the week before an election to sway voters,

because many already will have cast ballots. Plus, the

mail makes election-night results less reliable, Chapin

said, because absentee ballots must be counted, and

there are enough of them to change the election

results.

Then there’s the question of whether the U.S. Postal

Service can handle the ballots. The Postal Service,

which is consolidating about half of its locations over

the next two years, welcomes mail voting and assures

security and timely delivery, spokesman Peter Hass

said.

It delivered 99.7 percent of mail within three days of

the service standard, according to the USPS. The

remaining mail might have been delivered late, but it

probably was not lost, Hass said, describing loss as

“minuscule.”

For an emerging generation of voters born into a

digital world, mail might seem antiquated. Paper mail

has an established presence in elections, and

electronic mail is gaining a foothold. Internet voting

might offer the ultimate in convenience, but it poses

security problems that won’t soon be resolved, computer

scientists said.

A handful of Internet pilot programs have been tried,

and 31 states let primarily those in the military and

overseas vote by fax, e-mail or an Internet portal,

according to Verified Voting, a non-profit organization

that lobbies for verifiable election systems.

The more immediate future of the mail and voting

depends largely on cost, Chapin said.

Many think it makes little sense to keep a lot of

polling places open on Election Day when more people

are voting by mail or early. States might move entirely

to the mail, as Oregon and Washington, or scale back

Election Day voting, Chapin said.

“Jurisdictions are going to balance the services they

provide to voters in the same way an investor balances

funds in a portfolio: ‘I’m willing to spend x dollars

to get y percent return,’” Chapin said. “If it costs me

a lot of money to get just a few voters in person, then

I’m going to reduce my investment there and spend money

elsewhere.”

For comments or feedback, email news@news21.com