Flurry of Photo ID Laws Tied to Conservative Washington Group

A growing number of conservative Republican state

legislators worked fervently during the past two years

to enact laws requiring voters to show photo

identification at the polls.

Lawmakers proposed 62 photo ID bills in 37 states in

the 2011 and 2012 sessions, with multiple bills

introduced in some states. Ten states have passed

strict photo ID laws since 2008, though several may not

be in effect in November because of legal challenges.

A News21 analysis found that more than half of the 62

bills were sponsored by members or conference attendees

of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a

Washington, D.C.-based, tax-exempt organization.

ALEC has nearly 2,000 state legislator members who pay

$100 in dues every two years. Most of ALEC’s money

comes from nonprofits and corporations — from AT&T

to Bank of America to Chevron to eBay — which pay

thousands of dollars in dues each year.

“I very rarely see a single issue taken up by as many

states in such a short period of time as with voter

ID,” said Jennie Bowser, senior election policy analyst

at the National Conference of State Legislatures, a

bipartisan organization that compiles information about

state laws. “It’s been a pretty remarkable spread.”

A strict photo ID law, according to the National

Conference of State Legislatures, requires voters to

show photo ID or cast a provisional ballot, which is

not counted unless the voter returns with an ID to the

elections office within a few days. Less-strict laws

allow voters without ID to sign an affidavit or have a

poll worker vouch for their identity — no provisional

ballot necessary.

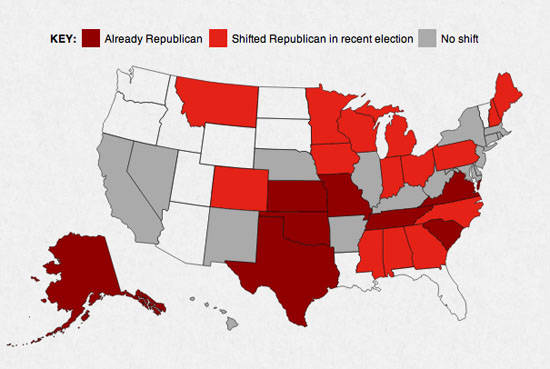

The flurry of bills introduced the last two years

followed the 2010 midterm election when Republicans

took control of state legislatures in Alabama,

Minnesota, Montana, North Carolina and Wisconsin. The

same shift occurred in the 2004 election in Indiana and

Georgia before those states became the first to pass

strict voter ID laws.

Click on the image to see an interactive graphic

detailing a group of state legislators who organized

to work on economic issues and later evolved into a

national body that is shaping election laws across

the U.S.

ALEC members drafted a voter ID bill in 2009, a year

when the 501(c) tax-exempt organization had $5.3

million in undisclosed corporate and nonprofit

contributions, according to Internal Revenue Service

documents.

At ALEC’s annual conferences, legislators, nonprofits

and corporations work together without direct public

input to develop bills that promote smaller government.

The group’s Public Safety and Elections Task Force at

the 2009 Atlanta meeting approved the “Voter ID Act,” a

photo ID bill modeled on Indiana and Georgia laws.

The task force convened in committees at the downtown

Hyatt Regency Atlanta that July. Arkansas state Rep.

Dan Greenberg, Arizona state Sen. Russell Pearce and

Indiana state Rep. Bill Ruppel (three Republicans now

out of office) led drafting and discussion of the Voter

ID Act.

Critics of photo voter ID laws, such as the Advancement

Project, a Washington D.C.-based civil rights group,

say voters without a driver’s license or the means (a

birth certificate or Social Security card) to obtain

free ID cards at a state motor vehicles office could be

disenfranchised.

They claim that ALEC pushed for photo ID laws because

poor Americans without ID are likely to vote against

conservative interests – a claim that authors of the

Voter ID bills deny.

“By no means do I want to disenfranchise anyone,” said

Colorado Republican state Rep. Libby Szabo whose ID

bills have failed the last two years in the state’s

Democratic senate.

“I can’t speak for each individual person,” Szabo said,

“but it seems to me in today’s mobile society people

have been able to manage transportation options for

other necessary services.”

Szabo, an ALEC member, said she did not know ALEC had a

model photo ID bill prior to submitting her

legislation.

Growing interest in ALEC

The late Paul Weyrich, a political activist and

co-founder of the Heritage Foundation, a conservative

think tank, helped start ALEC in 1973. For many years,

it steadily increased in state-level legislative

members, developed annual conferences and had a

relatively low national profile.

As ALEC grew, it began drafting and disseminating

“model bills” that advocated free market economic

ideas, such as eliminating capital gains taxes and

weakening labor and consumer laws. Its website states,

“Each year, close to 1,000 bills, based at least in

part on ALEC Model Legislation, are introduced in the

states. Of these, an average of 20 percent become law.”

This statement was difficult to substantiate until 2011

because ALEC’s model bills and membership lists were

secret. After Ohio community organizer Aliyah Rahman

helped start a spring 2011 protest against ALEC in

Cincinnati, someone offered her 800 ALEC documents.

Rahman, who said she never learned the leaker’s

identity, turned the documents over to the Center for

Media and Democracy, a Wisconsin-based investigative

reporting group focused on “exposing corporate spin and

government propaganda,” according to its website. The

group launched a website called ALEC Exposed in July

2011.

While that site drew attention to ALEC, activist and

media scrutiny exploded because of the council’s

support for model bills unrelated to economic issues.

In December 2011, ColorOfChange.org, a civil rights

advocacy group founded after Hurricane Katrina, began

asking corporations to stop funding ALEC because of the

group’s role in pushing photo ID bills.

The seeds of a more serious challenge to ALEC’s funding

were planted seven years ago. Florida Republican Rep.

Dennis Baxley, who in 2011 would sponsor the state’s

controversial early voting and registration changes,

sponsored a “stand your ground” law in 2005 that gave

“immunity from criminal prosecution or civil action for

using deadly force,” according to the bill’s summary.

It later became a National Rifle Association-supported

ALEC model bill, and 24 other states now have similar

laws, according to ProPublica.

The February 2012 killing of unarmed teen Trayvon

Martin in Sanford, Fla., brought unprecedented

attention to the law. Police did not arrest his

shooter, George Zimmerman, for nearly two months. That

sparked national protests and led to the dismissal of

the city’s police chief. Zimmerman eventually was

charged with second-degree murder in April and is free

on $1 million bond.

In March, ColorOfChange.org began asking ALEC corporate

funders why they gave money to a group that supported

“stand your ground” and voter ID laws, two

controversial non-economic issues.

More than 25 corporations, including Coca-Cola, Pepsi,

Wal-Mart and Amazon, have announced they would stop

funding ALEC.

“In a lot of cases, companies didn’t know the full

range of what they were funding (through ALEC),” said

Gabriel Rey-Goodlatte, ColorOfChange.org’s director of

strategy. “With voter ID, it’s possible some companies

believe it’s in their business interest to tilt the

political playing field in one direction, but that

would be a very cynical business strategy.

“It’s one that only works if it’s done in the

darkness,” he said.

Both the Center for Media and Democracy and the open

government advocacy group, Common Cause, have published

internal ALEC documents, including model bills,

membership lists and correspondence with elected

officials.

Common Cause is challenging ALEC’s status as a

tax-exempt nonprofit, claiming it lobbies legislators —

specifically through “issue alerts.” Common Cause

claims these emails from ALEC headquarters to state

legislators “constitute direct evidence of ALEC’s

lobbying because they are communications that are

clearly targeted to influence legislation and disclose

ALEC’s view on the legislation.”

Marcus Owens, a retired director of the IRS Tax Exempt

and Government Entities Division, represents a

progressive church group in Ohio called Clergy Voices

Oppose Illegal Church Entanglement, or Clergy VOICE. In

June, Owens sent a 30-page letter to the IRS alleging

that ALEC has engaged in lobbying and violated federal

tax law.

But Baxley called it “a healthy thing for legislators

to come together and have dialogue about bills.” He

said that ALEC’s operations are similar to, though more

conservative than, the bipartisan National Conference

of State Legislatures. “If they share ideas, I don’t

start yelling conspiracy. It’s very inappropriate,”

Baxley said.

Meagan Dorsch, public affairs director for the National

Conference of State Legislatures, disputed Baxley’s

characterization. “I’m not sure why we’re being

compared — probably because we’re two of the larger

legislative organizations,” Dorsch said. “The only

people who vote on our policies are legislators. No

corporate members are involved.”

Common Cause staff counsel Nick Surgey said the

documents his group sent to the IRS provide “a snapshot

of what ALEC’s been doing” from 2010 to 2012, but the

group has not come across any ALEC issue alerts related

to the Voter ID Act.

ALEC, whose staff declined to discuss the group’s role

in advocating for voter ID bills throughout a

seven-month News21 investigation, will not disclose

which corporations voted for the model voter ID bill

nor whether issue alerts were sent to states

considering such legislation.

“It is vitally important to protect the integrity of

our voting system in the United States and such

protection must come from the state level,” a July 2009

ALEC newsletter said. “That is why ALEC members are

actively working on these issues.

“Election reform is both critical and complex, with

multiple possible solutions for different states.

Therefore, ALEC is uniquely positioned to raise

awareness and provide effective solutions to ensure a

legal, fair and open election system,” the newsletter

continued.

Andy Jones (a former intern) and Jonathan Moody (still

an ALEC staff member) wrote that article. Jones

declined comment and Moody did not respond to an

interview request.

Sean Parnell worked with state legislators Greenberg,

Pearce and Ruppel when they drafted the ALEC model

voter ID bill (Pearce did not respond to multiple

interview requests). Parnell was then the president of

the Center for Competitive Politics, an Alexandria,

Va., organization that opposes campaign contribution

limits.

“A number of organizations — on all sides — are a

little too paranoid about talking,” said Parnell, who

now runs a consulting firm, Impact Policy Management.

“But you have to understand, as private entities, they

have every right to say, ‘You know what? This is not

something for public consumption.’”

“But I can tell you, ALEC private-sector members really

didn’t care one way or the other when we discussed

voter ID,” he said.

Ruppel said about 50 legislators and private-sector

members voted on the bill, with a wide majority voting

yes. “The private sector was a little quiet on it, but

they were the ones who said people need IDs for

everything these days. It’s common sense.”

News21 attempted to contact each of the 115 ALEC Public

Safety and Elections Task Force members listed on a

2010 document that Common Cause published. The majority

did not return phone calls. Former Michigan state Rep.

Kim Meltzer, one of 108 Republicans on the task force,

said she didn’t know voter ID was an ALEC initiative.

Georgia legislator Edward Lindsey said ALEC gradually

developed “mission creep” and strayed from its

economic-centered purpose. ALEC, facing intense media

attention and corporate dropouts, disbanded the Public

Safety and Elections Task Force in April.

“That should help them focus on core economic policies

instead of on the machinations of democracy,” said

Keesha Gaskins, senior counsel at the Brennan Center

for Justice at New York University School of Law, a

group that opposes strict photo ID laws.

Legislator interest in voter ID

It is difficult to find exact matches between ALEC’s

Voter ID Act and strict photo ID bills that appeared

nationwide in the past two years. Much of the minutiae

of the bills’ language differs, which Greenberg said is

the objective.

“That’s the way ALEC works. We don’t give people an

ironclad law to propose,” he said.

And because Greenberg’s bill was modeled on the Indiana

and Georgia laws, many legislators interviewed for this

story said their proposals were also based on those

laws, not ALEC’s model bill.

Still, the Center for Media and Democracy’s Brendan

Fischer said his group sees “pretty strong evidence” of

the influence of the Voter ID Act: “We identified

numerous instances where legislation introduced in

state legislatures contained ‘ALEC DNA’ — meaning the

state legislation and the ALEC models shared similar or

identical language or provisions.”

State bill sponsors, including Republican state Rep.

Cathrynn Brown of New Mexico, said their motivation did

not come from ALEC, but from reports about the

now-defunct voter registration group, the Association

of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN).

“We had groups like them going around doing

registrations and discarding the ones they didn’t

like,” Brown said.

ACORN, which endorsed Barack Obama for president in

2008, became the target of conservative activist James

O’Keefe’s deceptively edited videos that purported to

show employees encouraging criminal behavior.

ACORN folded in 2010 after Congress and private donors

pulled its funding. New Hampshire state Rep. Jordan

Ulery blamed the group for increasing partisan fighting

about election fraud.

“Are both parties guilty of games? Sadly, yes,” said

Ulery, a former member of ALEC’s Public Safety and

Elections Task Force. Ulery, a Republican, supported

his state’s voter ID bills, which have twice been

vetoed by the state’s Democratic governor.

“But only one political party in this past decade has

actually been widely associated with an entity that was

actively engaged in registration scams, trucking of

voters and avoiding with the greatest possible energy

vote-security measures,” Ulery said about Democrats.

Former ACORN director Bertha Lewis now runs a civil

rights group in New York City called the Black

Institute. She is still defiant toward ACORN’s

critics.

“Our quality-control program was so good, and we were

so strict, we would fire people on the spot,” said

Lewis, who estimated that ACORN registered more than a

million voters in 2007 and 2008 before Obama’s

election. “I only regret that we weren’t as prepared,

that we were naive when the critics started spreading

lies.”

After ALEC’s 2009 Voter ID Act, ACORN’s 2010 collapse,

and the 2010 midterm elections, 62 voter ID bills were

introduced in state legislatures.

Legislators who would discuss how they wrote their

bills all said they did not use ALEC’s Voter ID Act.

“I have a long history with this,” said state Rep. Mary

Kiffmeyer, Minnesota’s former secretary of state and a

Republican who wrote Minnesota’s voter ID bill. “For

people who say this is just ALEC’s bill is demeaning to

me as a woman and a legislator — suggesting that we

couldn’t write our own bill for Minnesota.”

Greenberg isn’t surprised lawmakers have dissociated

themselves from the ALEC model, given the recent

backlash.

“Some of that is legislative vanity that is not

confined to the realm of ALEC,” and Greenberg says he

“can’t imagine claiming that I don’t copy good ideas

when I see them, but I think for some legislators, this

would be a scary admission.”

For comments or feedback, email news@news21.com